It is curious what our Holy Week has changed in the last 20 years, in all aspects. One only has to consult any of the old recordings that many of us still treasure in our homes to verify that many things that we take for granted today, not so long ago, were new or did not even exist. For example, 20 years ago the Procession of Souls and the Via-Crucis of the Santísimo Cristo de la Sangre were groundbreaking novelties, today we do not understand our Holy Week without these two parades. Twenty years ago hardly anyone in Cieza knew about the work of Romero Zafra and now there are few who have not been amazed by the faces of the Coronation of Thorns and of Our Lady of Bitterness. The same goes for music. The soundtrack of our Holy Week has changed as much or more in the last 20 years than in the previous 50.

The question that arises from this reflection is: is this change good or bad? Asking this question is easy, answering it is not so easy. This issue is rooted in a philosophical controversy: the eternal dichotomy between conservation and innovation, which leads us to consider our own identity as a brother.

Perhaps the music does not generate this debate for some, because as long as marches sound in the processions and there are bands that play them, it does not matter if a march is Andalusian, Madrid or Levantine, or if it was composed a century ago or before yesterday, the important thing is that it sounds like Easter. The problem is precisely this, the problem of identity: what sounds like Easter to you?

If you ask a young person this, they will most likely cite marches such as "Bajo tu Amparo", "Caridad del Guadalquivir" or "Mi Amargura", while if the person questioned is someone of a certain age, it is quite likely that they will cite marches like “Mater Mea” or “Mektub”. I'm sure you'll agree that these two groups of marches sound very different, or, to be more precise, evoke different things. Also, if you ask a person from Cartagena the same thing, they will surely tell you about "Nuestro Padre Jesús" or "Solemnidad", but if you ask a person from Seville they will talk about "Coronación de la Macarena" or "Amarguras". With which, perhaps we should ask ourselves: what does Holy Week in Cieza sound like? We come to the problem of defining ourselves, to the problem of our own identity.

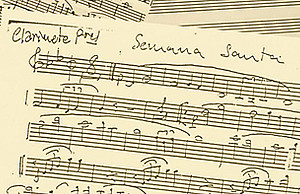

If we focus on history, if we look at what has been playing in Cieza for as long as there is evidence, we find the music of Maestro León and, later, the marches and pasodobles of Gómez Villa, all mixed with the marches that The solemn and funeral marches that refer us to the 19th century and to musicians such as Beethoven, Chopin and Wagner, in other words, the work of Emilio Cebrián, Mariano San Miguel, Ricardo Dorado and Miguel Pascual, have come to be called “classical”. among others. But, if you count from the year 2000, you will see that there is a change. That classic, funereal and solemn sound, seasoned with the freshness of the Murcian character, is gradually disappearing in the face of new trends: the marches of Andalusian origin, with a deep native Andalusian folkloric base, and the great "modern" marches or, better Said, “cinephiles”, since they are based on resources typical of film music.

Hence the title of this article. What's wrong with “Mi Amargura”? Well, this great march by Víctor Ferrer has become a symbol of this innovative current at a national level. What's wrong with all these new trends? Objectively there is nothing wrong. Musically they are great works, both those that transcend the borders of Andalusia and those that seek their sonority in the soundtrack. But to what extent are these works ours? To what extent do they remind us of our very particular Holy Week, the one that grew up lulled to sleep by the violins of San Juan and took shape at the hands of Gómez Villa? This is the real underlying problem.

However, it is counterproductive to go against the times. An excess of conservatism can lead to the death by suffocation of our traditions, while uncontrolled innovation leads us to this problem that I want to draw attention to with these lines: the loss of our identity. Are we willing to take that risk? A Holy Week that aspires to internationality cannot be closed to the trends that, after all, are the renewed face of this centuries-old tradition; but neither can it afford to lose its essence, those aspects that make it unique, that define it and make it stand out in its environment. Ours is a unique Holy Week, so special that it leaves no one indifferent, local or foreign. Perhaps it is time to consider this dilemma and find the perfect balance between modernity and tradition.